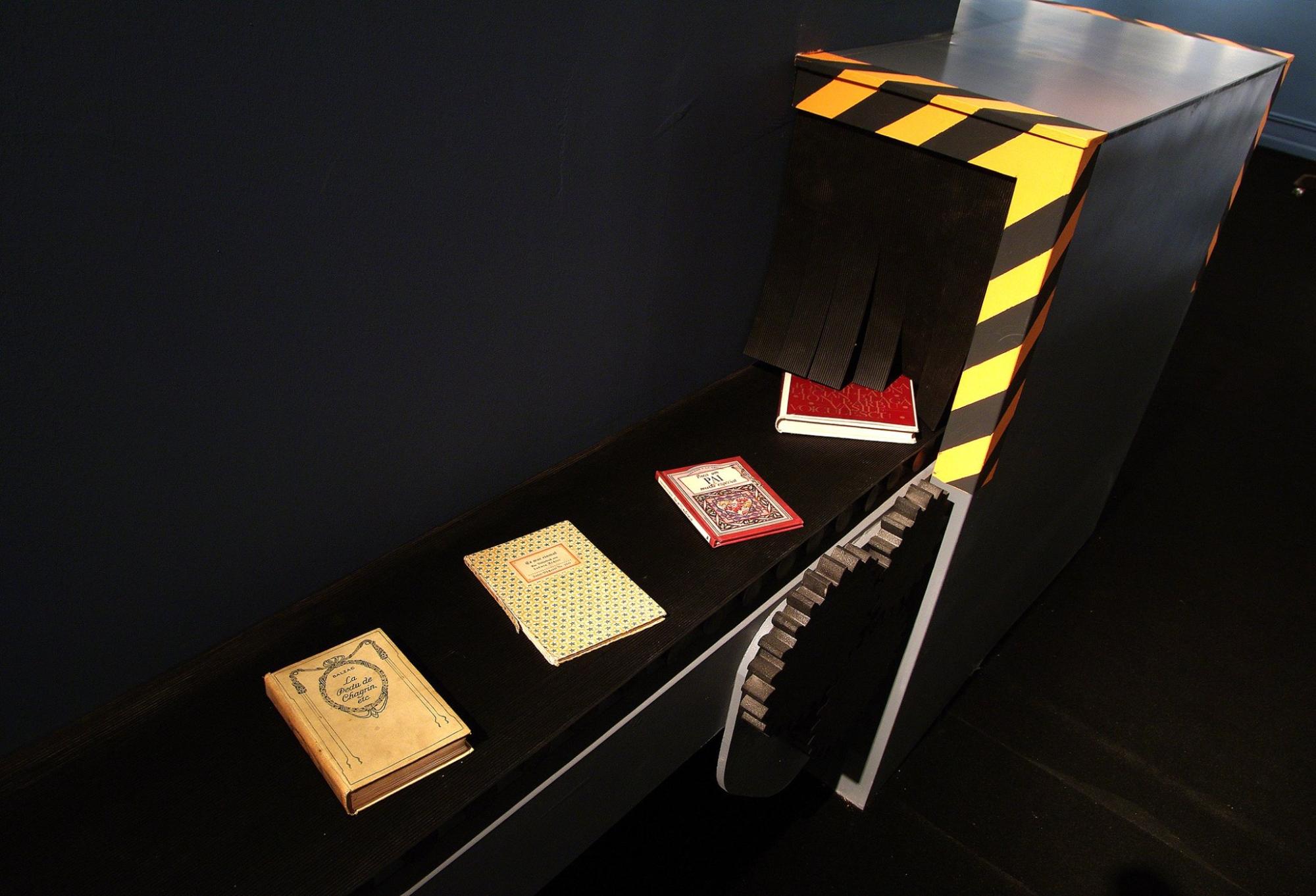

THE LITERARY TRANSLATION MACHINE

The exhibition invites visitors to look inside this machine. We’ll show how the automatic machine works. What stages does a text go through before it reaches the reader? What means are available for translators to understand the original text better? What methods do they apply and what devices may they create for themselves? We’ll present the diversity of translation, how different a foreign text may become in Hungarian and how different it could still be. We’ll look into the reasons why a literary work is sometimes translated several times. Moreover, we can even look into the dead ends of literary translation.

Let’s look inside this mysterious machine, how the LITERARY TRANSLATION MACHINE works.

THE RAW MATERIAL

Literature translated into Hungarian is the same age as Hungarian literature itself, since the first literary records in Hungarian are themselves translations. Those texts, however, are not works performed with an artistic ambition, thus they cannot be regarded as real literary translations. Yet there are translations of a high literary standard which are faithful to the text. Albert Szenczi Molnár was the first Hungarian translator who paid more attention to formal, contextual and aesthetic aspects. He translated from French with the help of German as an intermediary language – his psalms can already be regarded as real literary translations.

In the 17th and 18th centuries literary translations kept appearing mainly from Latin, German and French. Hungary’s inclusion in the Habsburg Empire and the strong attraction of the Hungarian intelligentsia to the ideas of the Enlightenment and French erudition all played an important role in that.

The age of systematic translation commenced in the 19th century. Hungarian translators placed world literature before them and set themselves the task of methodically translating with a high literary standard in mind.

A dictionary is a translator’s best friend or at least one of his or her most important tools. The slowly becoming extinct, although a few years ago still natural movement when you reach out for a dictionary as you come across an unknown word was not always natural. Hungary’s first bilingual dictionary, a Latin-Hungarian dictionary by Albert Szenczi Molnár was published in 1604. For a long time only a Latin-Hungarian bilingual and a Latin-German-Hungarian trilingual dictionary existed. The 19th century brought about the great breakthrough, and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences’ practice of systematically publishing dictionaries resulted in prosperity in the period after the Compromise of 1896.

The dictionaries indicated on the timeline do not present the entire range of publications – this exhibition would have to be much bigger for that. They only show the proportions and the character of dictionary development.

THE DRAWING BOARD

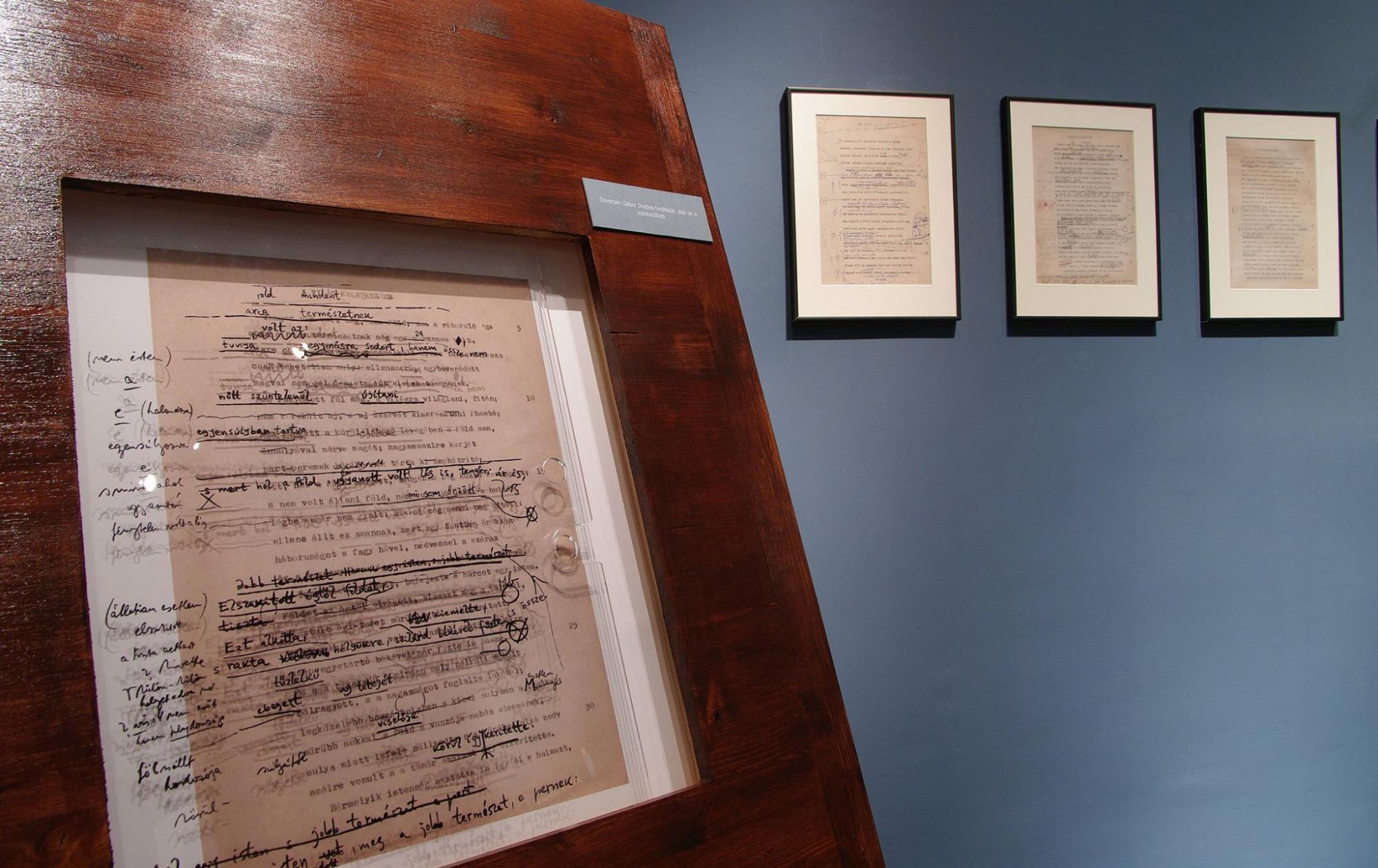

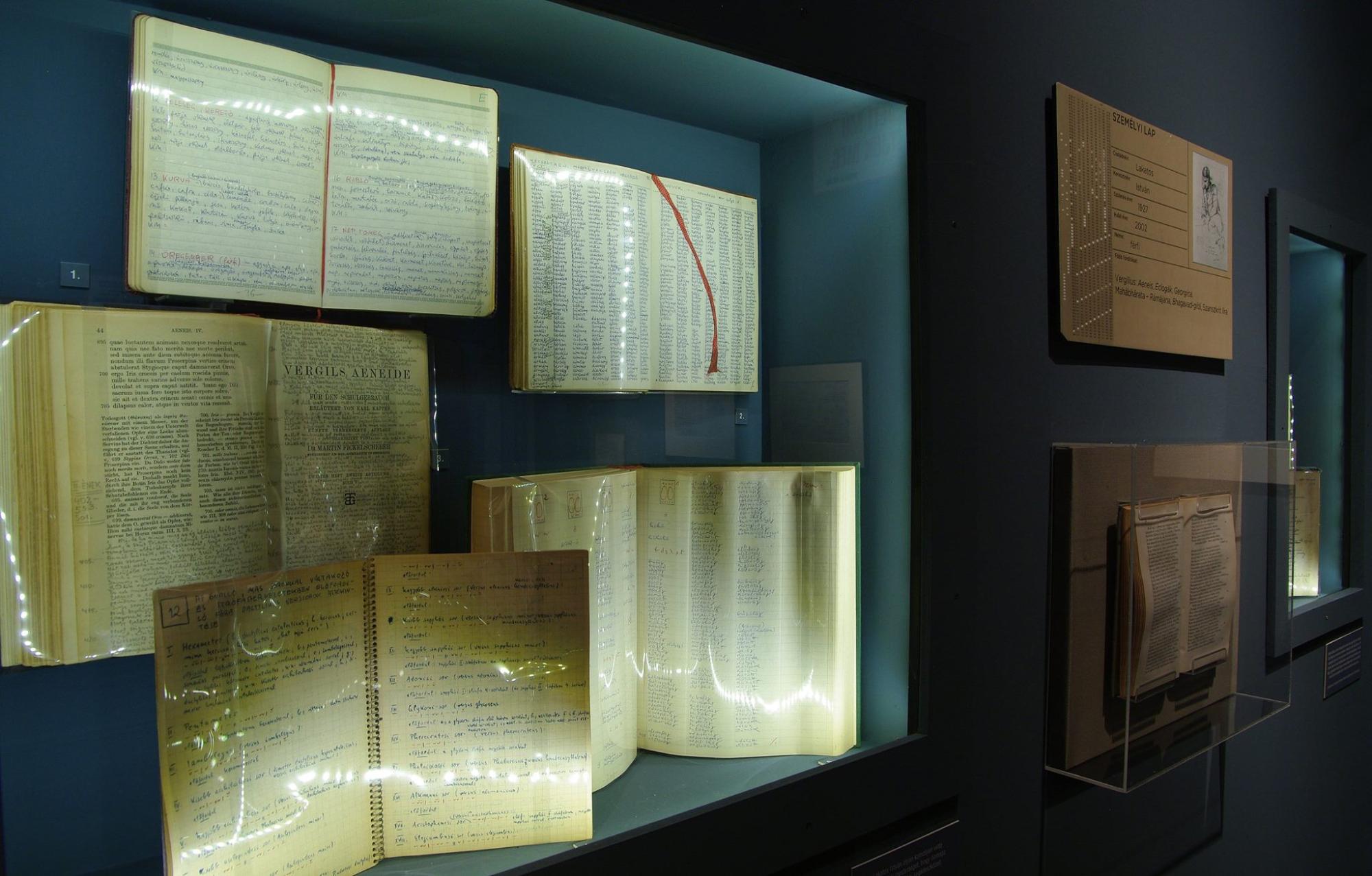

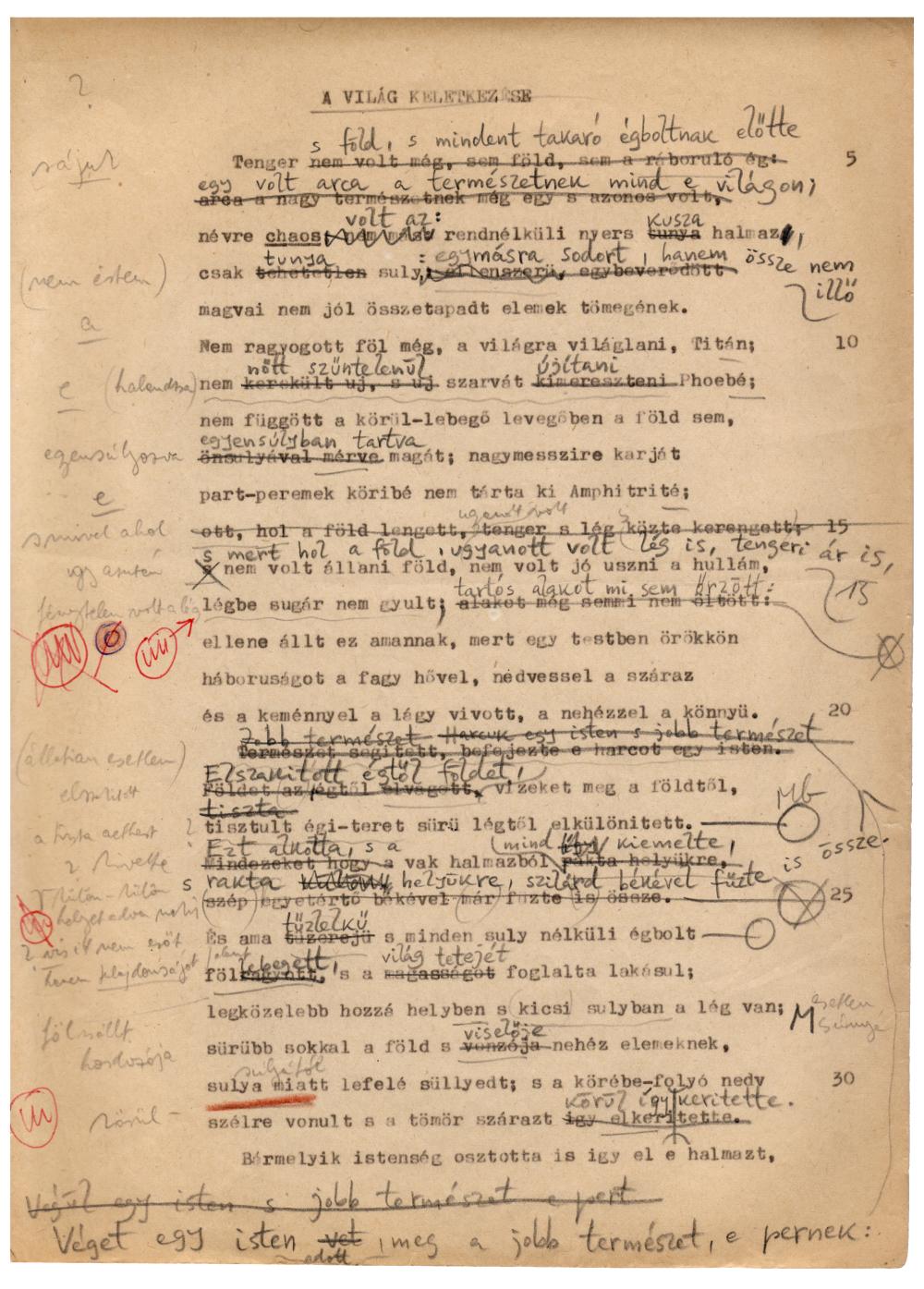

The most exciting part of literary translation is the inspired planning when the processed work receives either a new form or has to be fitted into a stranger’s original clothes. Creating texts of literature is a process exclusively shaped by the author’s own laws, while literary translation is a doubly determined activity due to its having two authors. It’s no wonder that forming a text requires a lot of planning, correcting and re-editing. Of course, the methods involved are not identical. Everyone sets about making a translation in their own way. This room presents five different procedures in literary translation employed by five prominent translators.

Lőrinc Szabó wrote down his translation notes for Mayakovsky’s poems in a small maths exercise book. He must have put together the first version in his mind because he put it down on paper in shorthand, not to let it slip from his memory. Then he rewrote it properly, first in pencil, then he made corrections, then in pen, and he again made corrections. Finally he typed them on small pieces of paper, which he pinned to the back of the exercise book.

István Lakatos took the craft of literary translation so seriously that he himself made his auxiliary devices for translating.

The first translator’s notes for the Aeneid

Gábor Devecseri was notorious for constantly making corrections. He typed Ovid’s Metamorphoses at least four times in full in order to perfect his text through newer and newer rounds of correction. You can see that he made ample corrections even on the printer’s proofs. According to one story, some printers presented him with a font so that he would set his own texts at home and not tire them with constant resetting.

Translators translate on every piece of paper at hand. The present documents show that Milán Füst used even letters written to him for the translation of King Lear, although the sender actually praised his translation.

Mihály Babits also made use of every blank or half blank scrap of paper. Similarly to Füst, he liked correspondence paper even if used, and even the smallest piece of scrap paper bore witness to his literary translator’s fantasy, as the scene of Dante meeting Giotto and Guido sketched in pencil shows. At the same time, as a conscientious editor Babits made final copies of the three parts of Dante’s Divine Comedy in three books (of these two are exhibited).

The manuscripts are from the collection of the National Széchényi Library.

THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY

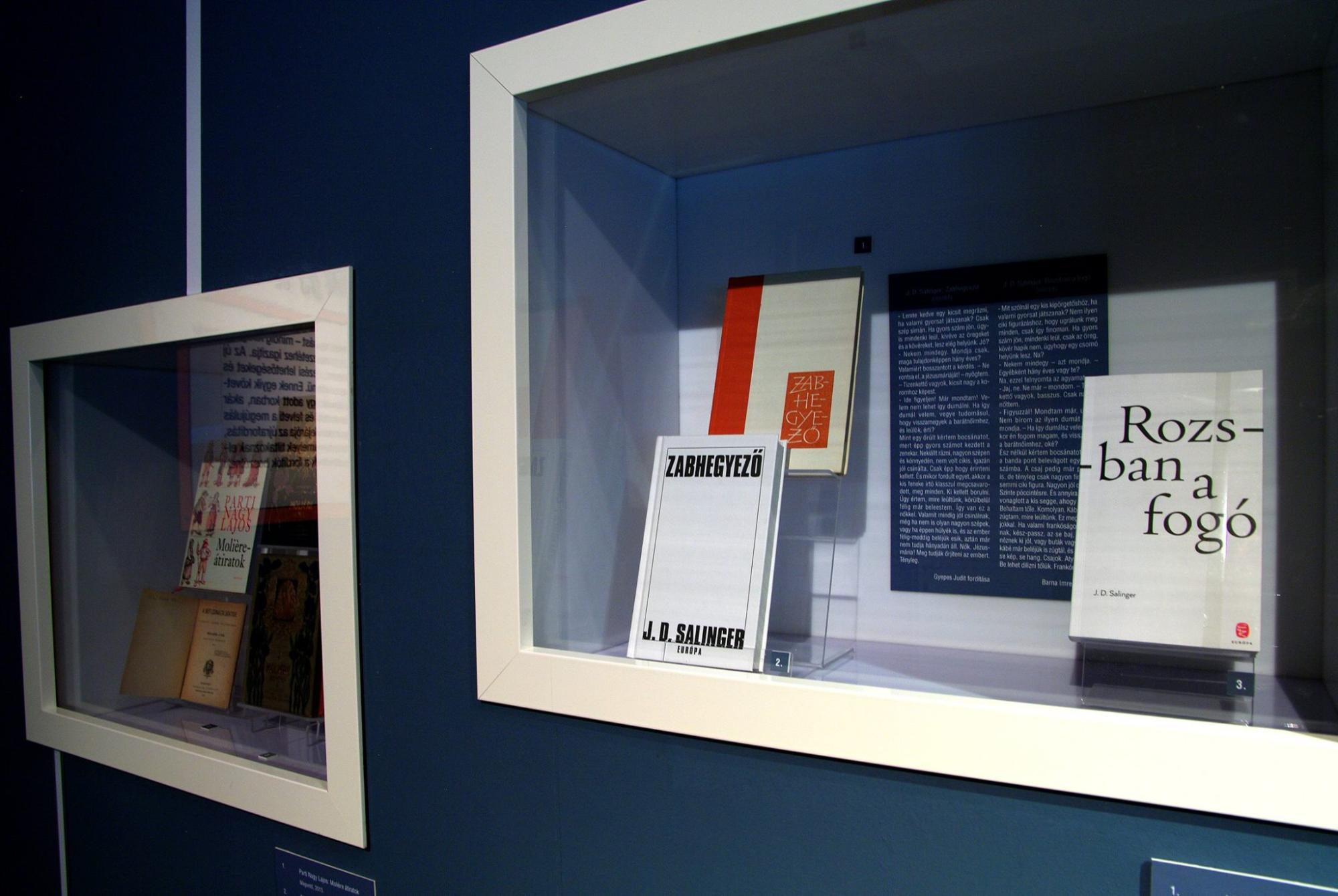

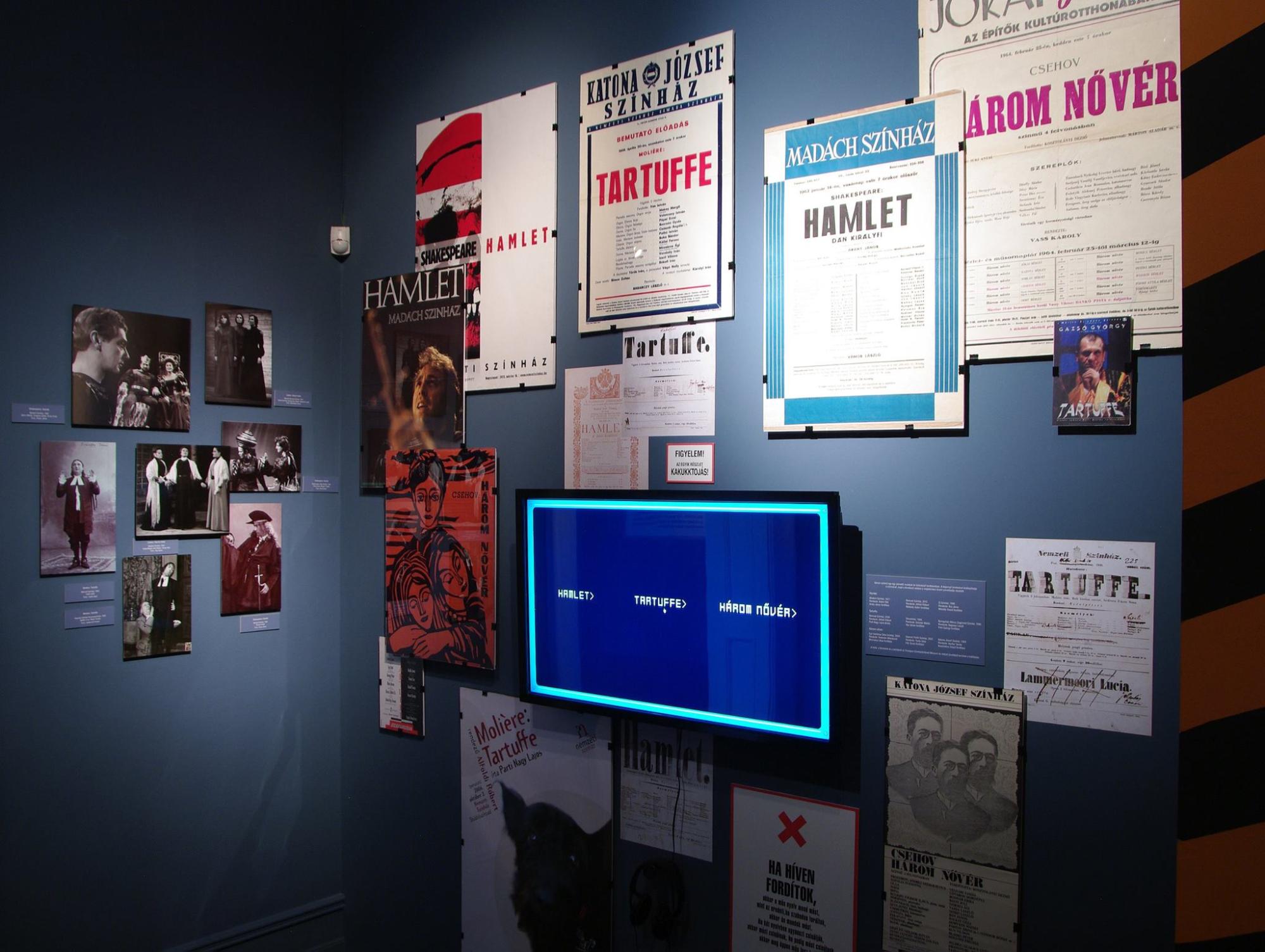

As seen with The Drawing Board, literary translators have to make constant choices. Although the journey is fixed, the ways of doing it are infinite. What choices a literary translator commits himself or herself to always depends on individual decisions of the moment. Accordingly, however narrow a translator’s toolkit may seem (especially in the case of poetry and drama) the same text may have several versions. A sample of this variety is illustrated.

The display screens show several translations of individual poems. We don’t claim that all the translations of any of the poems can be read here.

Milán Füst made comments on the translations by Dezső Kosztolányi and Lőrinc Szabó.

A scene from three plays can be seen in different translations. By touching the screen you can select the play and on the next page a part of the performance you wish to view.

The photographs, recordings and the playbills are exhibited thanks to the Hungarian Theatre Museum and Institute.

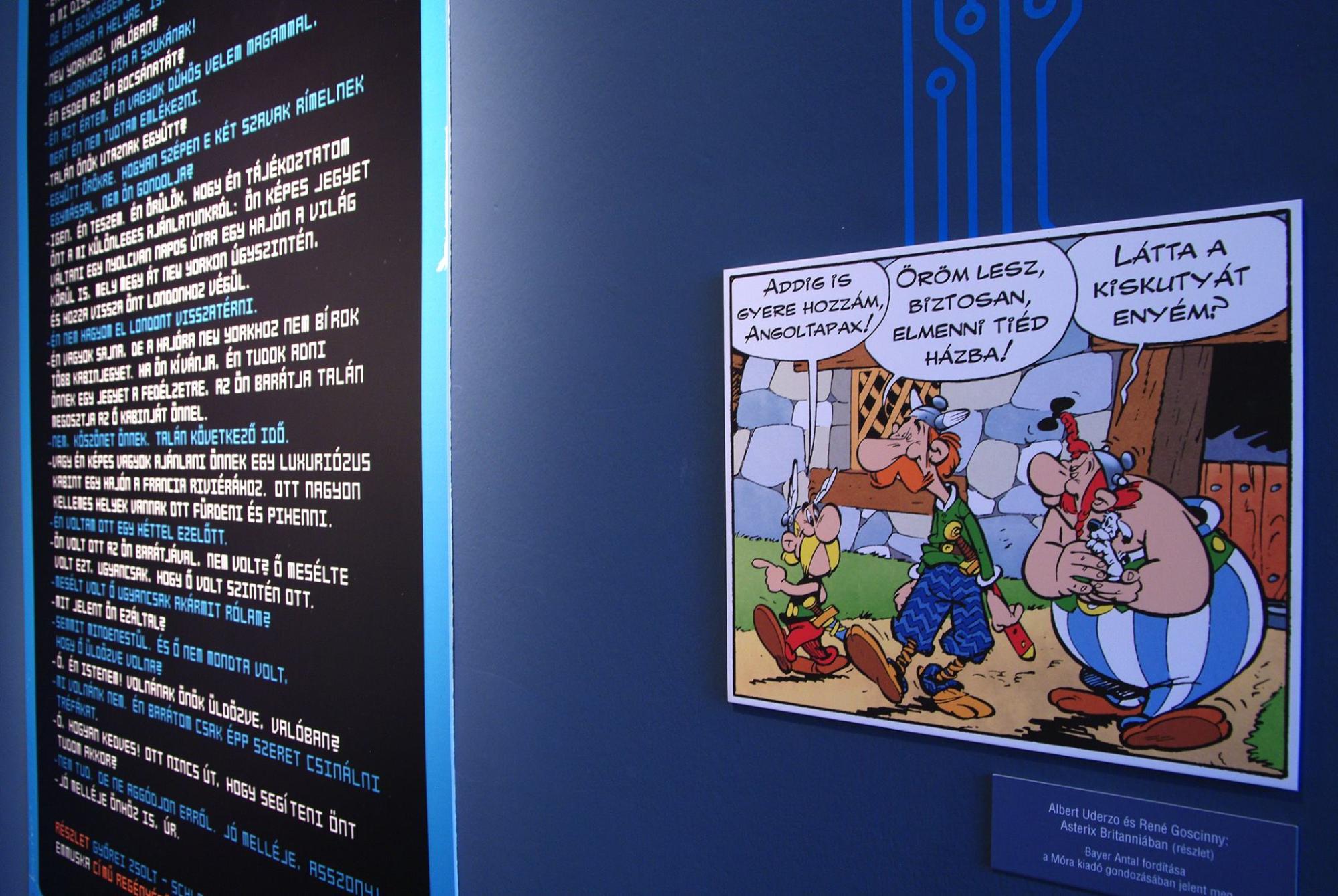

A BRIEF HISTORY OF COMPUTERISED TRANSLATION

Three major periods can be identified in relation to using computers for translation. The first, between the 1950s and 1970s, focused on mathematically grasping grammar. The second, from the 1970s to mainly the 1990s, can be considered the period of translation systems based on grammatical analysers. The achievements have been used for systems applying statistical translation, which have indeed worked in the past 20 years. Many experts think that the next step would be to perfect translation systems by modelling understanding via the computerised analysis of meaning.

SPA Quadro digital computer made in Hungary (1985)

In the 1960s in the then state-socialist countries the supply of computers was based on devices developed in the Soviet Union, but this type of activity was not supported in other countries. Thus in order to avoid the accusation of using outlawed computer development, Hungary’s Central Research Institute for Physics (KFKI) began manufacturing the Stored Programme Analyser (SPA). Quadro, which was developed in 1983-84, belonged to the SPA family. It was the Institute’s own development – not a copy of a western model – a compact, multiprocessor desktop device. It was known as the sewing machine due to its shape and it won the Hungarian Industrial Design Award. All in all, 120 were made.

The computer is from the collection of the Hungarian Museum of Technology and Transport.

TRANSLATORS AT WORK

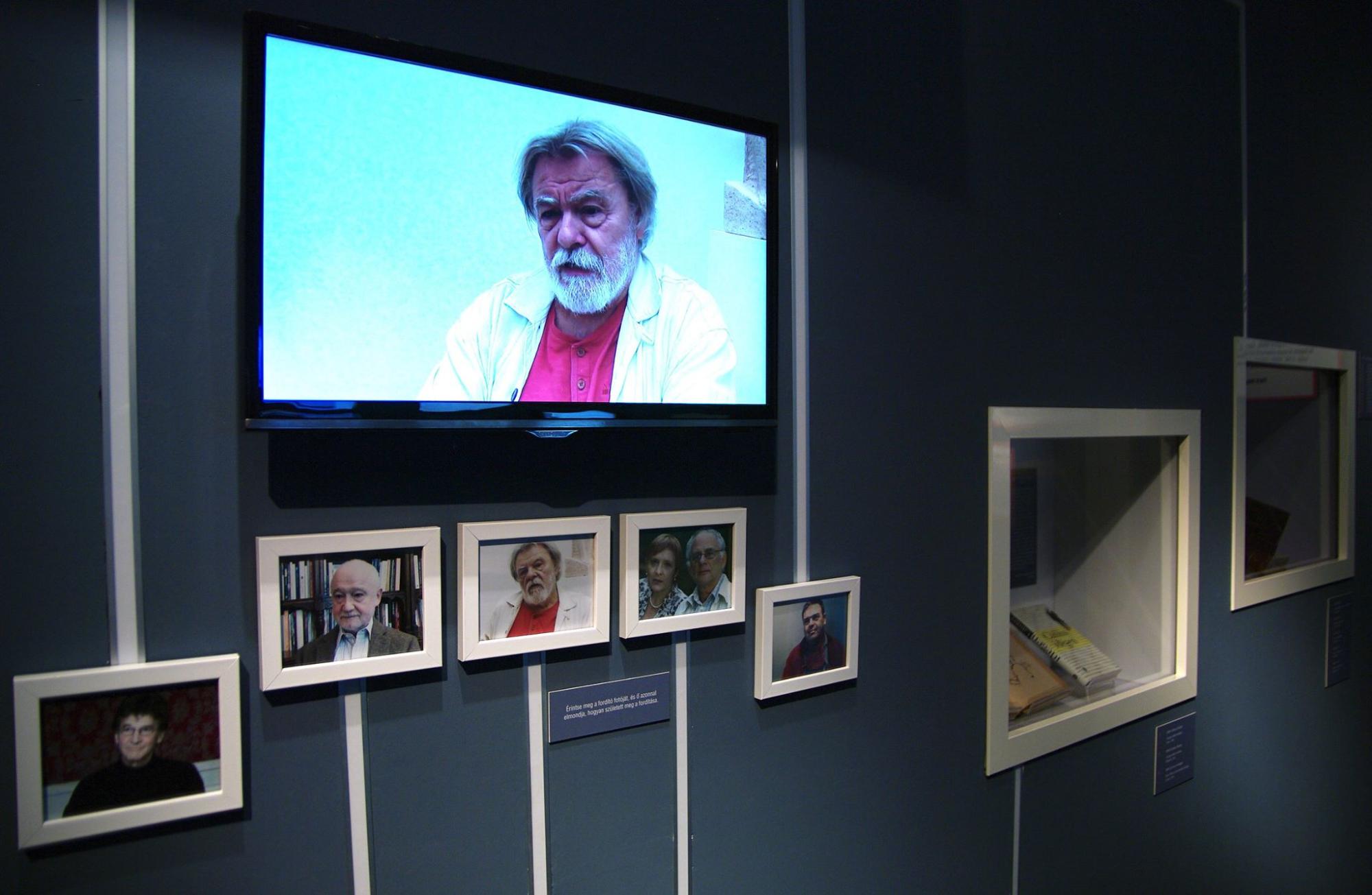

So far auxiliary tools, books, dictionaries, the methods, traditions and principles of translation have been discussed. A translator’s real work has only been approached. Hence the screens in this room show literary translators in “live combat”. You can observe the rhythm of their work, what they use, their pensive look as they stare at nothing, hoping to find the solution there. But most of all you can witness the birth of a text. The short films have been speeded up and edited (leaving out the periods of unavoidable although not always unproductive idleness) so that the ready translations would be available as soon as possible.

THERE IS ALWAYS SOMETHING NEW

Since they cannot do anything else, translators always take a text out of its original environment and adjust it to their own. The translated work receives a new cultural space, opportunities of new interpretation and perhaps a new era. As a consequence, what is regarded as new in a certain period may become obsolete even half a century later, thus from time to time the demand for a new translation arises. Although in principle this is a natural concomitant with translations, it sometimes evokes fierce protest. In this part of the exhibition translators themselves talk about their motivations.