The introduction of dragons emerging in a variety of appearances facilitates a versatile approach. The exhibition offers an interpretational opportunity from the perspective of literature: it outlines how different cultures have understood dragons, it introduces the attempts to describe them ‘scientifically’ and presents their extremely fertile presence in the fine arts. The selection invites a dialogue between the several-thousand-year-old cultural historical and literary traditions of dragon presentations and contemporary art and literary works, which shed light on the achronism of the dragons’ symbolic figure.

A compound creature

The dragon is a compound creature. Its body resembles a snake, its wings are like those of a bat, its claws resemble those of a lion, while its temper is similar to a greedy or angry person. It is compound because the dragon of our age fuses the characteristic features of a culture which is far away, both in time and space. What is thought of the dragon figure today is the result of a long cultural development and combination over many thousands of years. Its deeds and features cannot be interpreted in themselves, only with the help of other, related phenomena.

The dragon is a complementary figure. Its pair that defines it is the aggrieved, the kidnapped, the offered or the tormented victim, just like the valiant hero who is nearly always triumphant, albeit at the price of a fierce struggle.

Beasts lying in ambush at very corner of the world and the variety of concepts relating to them bear witness to the extremely diverse relationship of people with the progress of time and the grandiose natural and social phenomena.

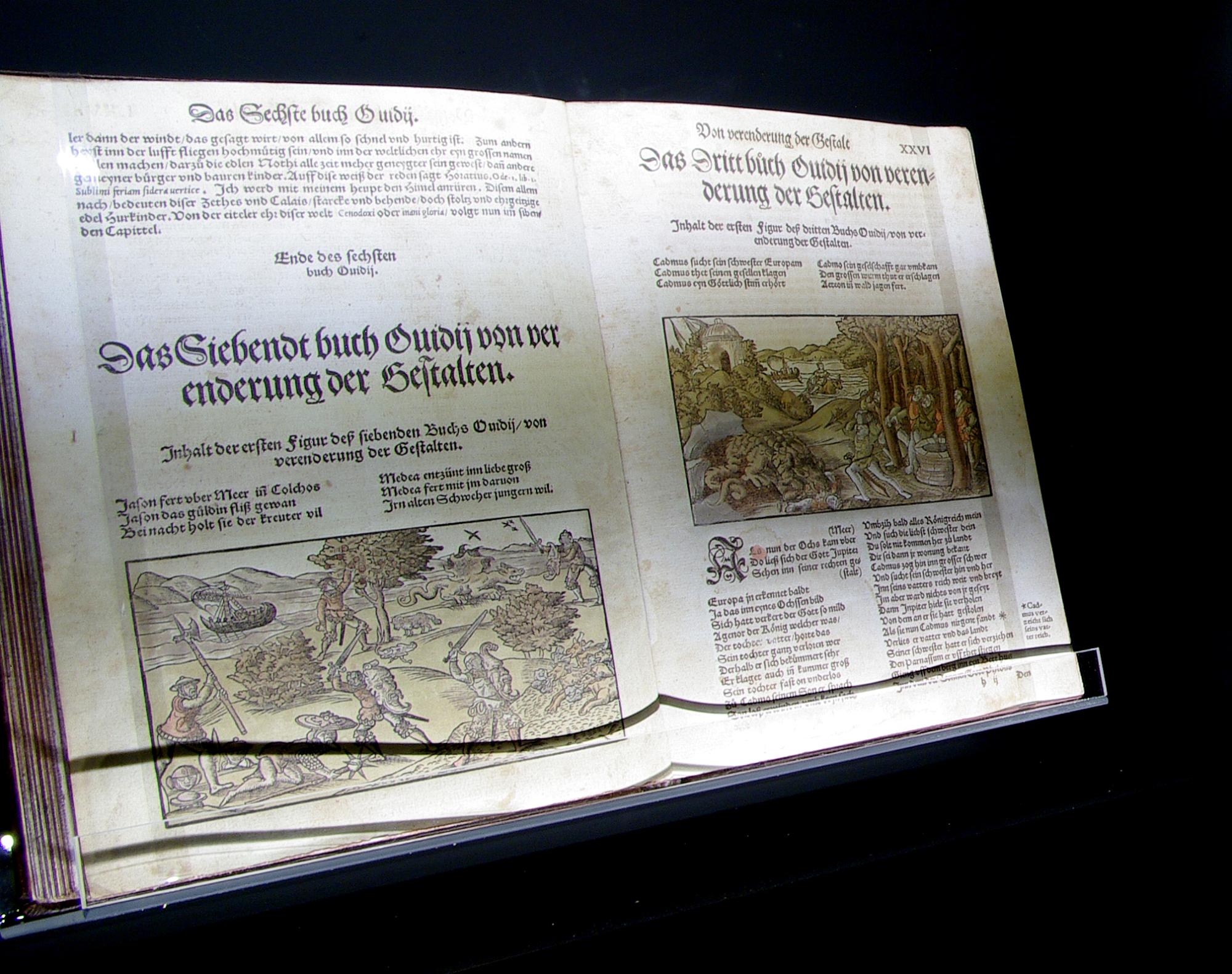

Fiery intemperance

Medieval bestiaries were treatises which provided a description and allegorical interpretation of real or imagined animals. They are thought to have evolved from a work entitled Physiologus (The Naturalist) which was written in Greek in the 2nd century. Besides the physical introduction of a natural phenomenon, the brief, didactic descriptions also explored their moral and religious meaning. Dragons introduced in bestiaries were embedded in people’s minds to such an extent that they petered out even from later naturalist books only at the time of Enlightenment. Thirteenth-century works already contained detailed descriptions of dragons. According to these a dragon (draco) is a generic term for creatures included in the category of reptiles. They usually occur in warm climates, primarily in the territory of Ethiopia and India. They are aggressive creatures emitting a sound which is so fearful that whoever hears it drops dead. Spewing fire, their breath poisons the air and thus epidemics break out. The elephant is its natural enemy. Since a dragon is always thirsty and its body temperature is high, it cools itself with elephant blood.

A remarkable opponent

The dragon of folk tales was imagined as a giant lizard with scales and sometimes with wings. Multi-headed human-type dragons ride, wrestle with the hero in a human manner, fighting with a sword, wielding a mace and drinking wine by the barrel. The most ancient motifs in tales are characterised by oriental features. In the Topless Tree stories the dragon kidnaps the king’s daughter in a tempest and takes her up to its realm on the top of a tree reaching to the skies. In another ancient layer of the tales, the dragon lives in a castle that twirls on the foot of a bird in the underworld. The dragon plays a role as an enticing man in the type of The Unfaithful Mother tales. Its anti-mankind actions affecting the whole community and with a cosmic significance are expressed in types of tales such as Duel on the Bridge and The Liberator of the Planet. The story of the water-guarding dragon features in the folk poetry of all the world’s peoples. There the seven-headed dragon demands human sacrifice from the community in exchange for water.

Well-meaning dragon-in-laws sometimes help the hero. In The Simple-minded Monster tales a stupid imaginary creature with supernatural features and a crafty man face each other.

The surviving type

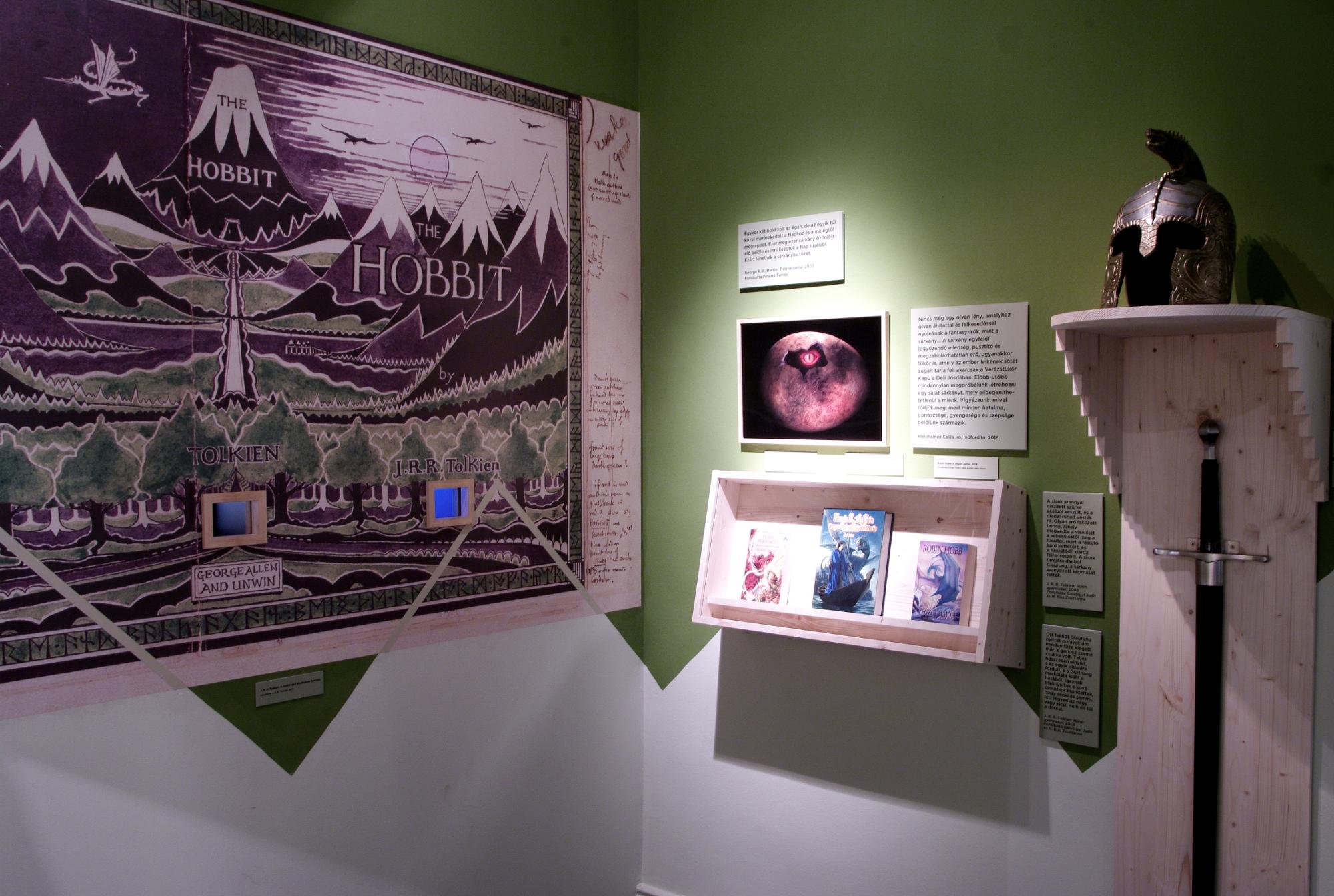

Fantasy fiction is almost unimaginable without dragons and their descriptions are extremely varied. In this respect J.R.R. Tolkien popularised the dragon and raised it to a literary rank in his novel The Hobbit, published in 1937. Dragons, who are intelligent although dangerous beings, symbols of evil to be defeated, also appear in his other books, such as The Silmarillion and The Children of Húrin.

Since the 1960s the approaches have become increasingly specific and the attributes of the dragon have changed. In the cycle of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin dragons are presented as the counterpoint of mankind. They are wise creatures who represent the last keepers of old values in a declining world.

Prominent writers of contemporary fantasy including Robin Hobb, George R.R. Martin and Sir Terry Pratchett approach dragons in a novel way. In their works dragons simultaneously represent ancient fierceness and elated intellect. They raise the issues of humanizing dragons, or with their help mankind is shown what it is truly like.

Dragon children

The funny or cunning dragon in children’s literature no longer behaves according to the folk tale scheme. A “human” dragon character is born with whom you can compromise. In Edith Nesbit’s novel The Last of the Dragons the dragon in no way feels like having a tournament. It rather desires some true kindness and a sip of petrol. That is how the last gentle dragon becomes the first aeroplane of the kingdom.

Since the 1970s dragons have also grown tame in Hungarian children’s literature. In Ede Tarbay’s The Story about a Dragon Turned Park-keeper the dragon seems lost and has to find a job which matches its character. The role is reversed in the story Süsü the Dragon by István Csukás. The one-headed dragon child who is mocked and deemed to be excluded proves to surpass its folk in wisdom and smartness.

The dragon does not appear as clearly evil in children’s fantasy either. In Sándor Török’s The Little Boy Falatka’s Kingdom the boy is drawing the fire-breathing dragon and the gentle Prince Árgílus amidst wonderful, cloudy, red, green, blue and black swirls. They do not fight with each other at all. “Here you have the good and the evil. Can you see? As it is, they are mixing...”

Divine monster

The most ancient dragons appear in the world of myths surprisingly naturally. Although their figure and features are quite super-human, their existence and origin are in harmony with the general order of the world: they incarnate natural phenomena and universal laws. They play their role amidst dichotomies such as sky and earth, winter and summer, existence and death, and are characteristically connected to the shaded side of a balanced, bipolar world order.

Keeper of treasures

In several stories dragons own, keep or steal treasures which are valuable for humans. The treasure may be a feature, condition or an object. Its chief attribute is that it is very desirable for people, but even sometimes for gods. Only a few apt heroes who defeat the keeper of the desired treasure, the terrible monster, are able to acquire it.

Ancient enemy

All the cyclical and dualistic concepts of the universe were gradually relegated to the background with the spread of Judeo-Christian culture. Following this changeover, the powers of darkness and evil are no longer counter poles of light and good. They play a far more subjugated role. Although in the Old Testament the image of an ancient figure from before the time of the creation of man still appears, most dragon-like creatures are the tools of evil powers, moreover the incarnation of revolt, and thus are to be rejected and can be finally defeated.

Harmful beast

The figure of the dragon has always provided an excellent opportunity for people to offer an explanation for the origin of place names and natural phenomena, and to relate to the negative experience of their immediate environment. The elements in beliefs, legends and tales, which connected one type of dragons with the wind, hail or lightning, are thought to refer to the dragon’s ancient origin as the “storm demon”, or the “celestial divinity” possessing the waters in the sky.

A worthy symbol

In Europe, for centuries the dragon’s figure was not only a favourite motif of decorative design, but also an effective means of expressing political representation and belonging to a group. The first secular chivalric order and later its revival, the Order of the Dragon, chose an ideal and a system of symbols embedded in the cult of Saint George, which also flourished in Hungary. In the Middle Ages the dragon was the symbol of heathenism, heresy and opposition to the ruling power. Later its figure became individualised and transformed into the emblem of human features to be overcome. The destruction of the dragon, which is supposed to be either real or symbolic, highlights noble features which stand up against the colossal opponent and the fighters who possess such attributes.

Strength and well-being

Although the specific figure of the hero who is able to fight with the dragon is also known in the Far East, the Chinese dragon is generally not thought to be negative. It exists in various forms and is usually considered as an amiable divinity with human attributes. Positive concepts such as strength, peace, flowering and wisdom are connected to its figure. It is undoubtedly an ancient totem, the symbol of the emperor for more than 2000 years.

Dragon of the soul

I can assert that everyone has already met a seven-headed dragon and a magic steed. True, the seven-headed dragon is called the boss, sometimes the mother-in-law or the worse ego of ourselves, while the magic steed is referred to as a Master or intuition. The glass mountain is considered the invincible pile of problems, which it is difficult to get a grip of. The rocks are thought to be the opposite movement wearing out the Ego, while the golden bird is seen as, for example, youth or health, and the water of life as the essence of a desired situation in life.

Ildikó Boldizsár

Dragons have never played any role in my life because since my childhood I regarded the dinosaurs as long extinct, real living beings and I wanted to learn about their biology as much as possible. That is why I became a biologist. Yet I absolutely understand that dinosaurs appear almost as mythological monsters in people’s imagination ... Many of the first discoverers of enormous dinosaur bones reconstructed the former owners of those bones as dragons.

Edina Prondvai, biologist, member of the Hungarian Dinosaur Expedition

I have written about creatures of which science knows already a little, or still little, and mostly of those whose existence is unproved or altogether unacceptable for the tribunal of zoology as a science. Science often says “no” with the short-sightedness of the “faithful believer”. It turns its back on certain problems, while the aim should actually be unprejudiced analysis.

György Szemadám, painter, author of The Book of Incredible Beings

In the headquarters of the Transylvanian Museum Society in Cluj I viewed the palaeontological sensation – the skeleton of an ancient reptile – which represented a huge palaeontological discovery at the beginning of the 2010s. On looking with wonder at the bones, an old text by an Italian historiographer, Ransanus, came to my mind: “There are caves in Transylvania ... and I have received a dragon’s head as a gift.”

For a long time specialist historians thought that it may have been the skull of a 10,000-year-old cave bear. On the basis of sources, I came to the conclusion that the possibility of the bone kept on Ransanus’s desk being actually a “dragon’s skull” cannot be excluded.

Gábor Farkas Farkas, historian of science

I have been thrilled by dragons since my childhood. I am likewise fond of scaly, black monsters, and of many-headed, fire-breathing red beasts who kidnap virgins, and gas-blowing, ivy-green brutes with a hypnotic look. It is knights alone who I hate for they keep killing the dragons for the sake of marrying some princess whom they usually don’t even know. It is not dragons we fear but what they represent, the elements, darkness and the unknown. I thought that if I brought the figure of the dragon closer to people I might be able to resolve their anxiety.

Bea Selmeczi, dramaturge, compiler of the performance Chronicles of Dragons

The story does not say that it is enough to regain what you have lost, but that you must fully get even with what endangers your “entirety”. If you have mercy on the dragon begging for the safety of its last head, you lose the thread of your life.

Ildikó Boldizsár, master therapist

The aim of what is frightening in a tale is for children to manage their traumas symbolically and abstractly. That is how they fight their own triumphant battles with dragons, the cruel stepmother and the formidable giant, because, after all, children win at the end of the story. Dragons, the cruel stepmother and the giant threaten them in reality, too.

Marcell Jankovics, graphic artist

The dragon is an ancient symbol of spiritual energy and an instinctive driving-force. An endless struggle with the dragon is a metaphor of a battle fought for inner improvement. We have to thank our foes for helping us to step over to the next developmental stage of our spiritual and intellectual journey and as a platform for projection it is for us to handle and see them as dragons.

Mária Feuer, psychologist