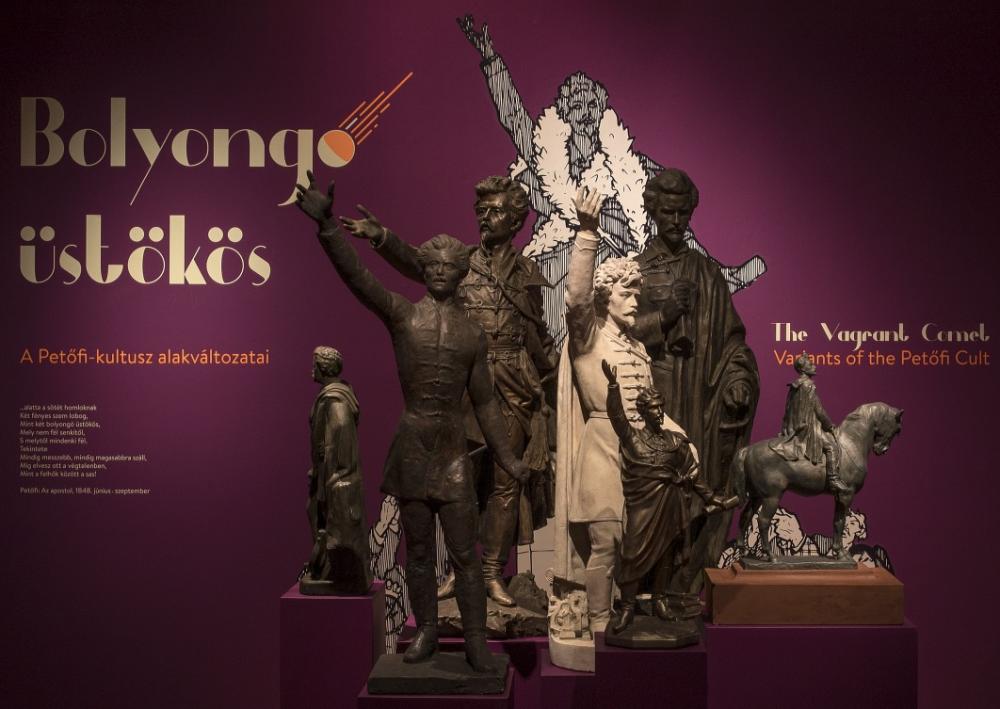

The exhibition seeks to address the issue of how the figure of Sándor Petőfi, “the poet” preserved in the national memory, has developed and changed over the past 170 years.

The exhibition title is from the self-characterisation of his poem The Apostle: “... below the sombre brow / two smouldering eyes flicker / like two vagrant comets / which fear no one / but are feared by all. His gaze / soars always farther, always higher.”

The variants of the Petőfi cult are represented by works marking the four prominent anniversaries (1899, 1923, 1949, 1973) which often involved state competitions or communal commissions. Works of art, paintings, statues, graphic art, special editions and publications for the occasion, as well as memorial speeches render the four eras, and have primarily been selected from the rich collections of the Petőfi Literary Museum. A sample of Petőfi’s image developed in the public and private spheres, along with its polyphony is presented. The works of art span the periods from the tradition of Hungarian historical painting (Viktor Madarász) through the younger generation committed to the principles of 1848 (János Thorma, László Hegedüs, Gyula Rudnay and István Csók) and then the artists whose oeuvre rose after World War II but were pushed into the background (Béni Ferenczy, Tibor Csernus and Béla Kondor) to those who are still successful and who, in the tense atmosphere of 1973, as young artists demanded a breakthrough in the spirit of Petőfi (László Lakner, Dóra Maurer and Endre Tót).

In the decades following the defeat of the 1848-49 Revolution and War of Independence the theme “Petőfi’s death” was identified with the idea of the nation’s death and was banned, appearing only in pietà-like allegorical representations. After the 1867 Compromise, the cult of the civil hero was presented primarily in popular graphic art and sculpture, as well as in a few monumental paintings. The most well-known example is My Homeland (1875), painted by Viktor Madarász. Although it received much criticism, it was extremely popular among the broader public and was spread through oleographs and traced drawings.

Along with the Bem-Petőfi cyclorama (1897), the monumental films made in 1914 and 1922, as well as the films The Whole Sea has Revolted (1953) and Petőfi ’73 help us to understand the system and ideology of the individual eras.

These high-quality artworks are supplemented by various popular genres on the borderline of art history, examples of exciting, often kitschy applied graphic art, as well as souvenirs and folk wood carvings made for anniversary celebrations, which are important imprints of the erudition and visual culture of the periods. A rarely exhibited selection of photographs and films helps in looking back at the atmosphere of the Petőfi celebrations during these four eras and in rendering reality as opposed to artistic vision.

An event is transitory, yet an anniversary and the gesture of celebration themselves are eternal and indestructible. The forms of commemoration may be platitudinous, moreover awkward. Mihály Babits wrote on the centenary of Petőfi’s birth: “...his celebration is a blind one, and in the narrow corridors of present days the words are ablaze as cheap candles.” Nevertheless, we trust that the examples will urge visitors to regard the Petőfi celebrations of the bygone past and the present differently by discovering the confessionary works concealing intimate encounters.